(Note: This is an updated version of an article I originally wrote for the June, 2005 issue of "THE SOUND BOX," (now titled THE ANTIQUE PHONOGRAPH) the journal of the The Antique Phonograph Society.)

There were hundreds of phonograph dealers in the 1890s and early 1900s but none

have attained the almost cult status of Peter Bacigalupi. It is something of a mystery

why Bacigalupi, more than any other dealer, so fascinates collectors today. Certainly

his San Francisco store was one of the largest and most important in the country,

but there were many other major dealers who are barely remembered today. Henry Babson's

Chicago-based business rivaled Bacigalupi's in size and market power, but while Babson's

name is at least somewhat familiar to collectors today he doesn't inspire the fervor

that Bacigalupi does. And what of Lyon & Healy, Kipp Bros., Vim Co., Eastern

Talking Machine Co., Grinnell Bros., Victor Rapke, Blackman Talking Machine Co.,

C.J. Heppe & Son, and McGreal Bros., among others? All were potent businesses

at the time but their legacies are barely felt today. And, as far as I know, no one

actively collects their memorabilia. It is understandable why collectors here in the San

Francisco Bay area might be intrigued by Bacigalupi, but it is less clear why collectors

throughout the United States, and even France and Germany, compete heartily to obtain

anything carrying the his name. For whatever reason, Peter Bacigalupi has captured

our imaginations.

Although Peter Bacigalupi sold Graphophones and other entertainment

devices from a number of companies, his name is particularly intimately connected

with Edison. Bacigalupi was the leading Edison jobber (wholesaler) in the western

states, as well as the single largest dealer in Edison goods – not just phonographs.

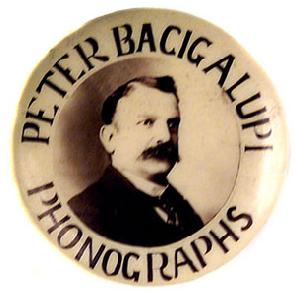

Peter Bacigalupi as caricatured in Talking Machine World, and pictured on a contemporary pin-back button.

Born in New York on January 6, 1855, Bacigalupi moved to San Francisco at an early

age. He later went to Peru, where he opened a business in Lima in 1881. During a

visit to the Chicago World's Fair in 1893 Bacigalupi met the dynamic phonograph pioneer

Leon Douglass, a leading figure in the business in Chicago in the 1890s. Douglass

sold phonographs and Kinetoscopes, invented and marketed the Polyphone attachment

in 1898, and later founded the Victor Talking Machine Co. in partnership with Eldridge

Johnson. Bacigalupi was excited by the Edison Class M electric phonograph and arranged

to buy some from Douglass for sale in Peru. (Douglass and Bacigalupi later became

close friends and even relatives by marriage – Douglass married Bacigalupi's step-daughter,

Victoria.

Clearly, Bacigalupi had found his niche.

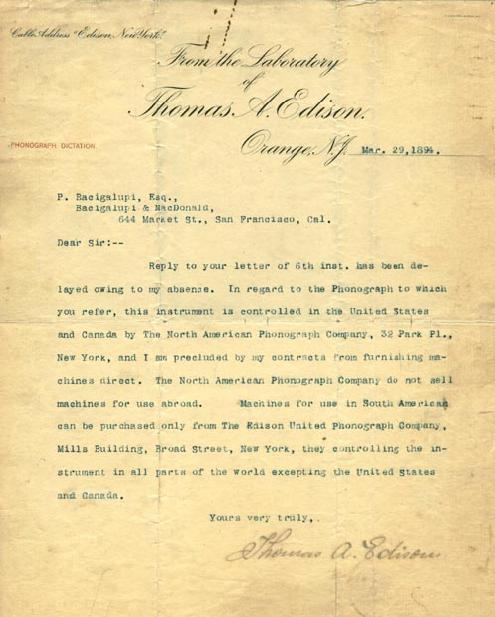

Returning to San Francisco a few months later, Peter Bacigalupi wrote to Thomas Edison

on March 6, 1894 to inquire about purchasing phonographs directly from the factory

for export to Peru. Edison's reply has only recent been uncovered, and it shows that

initially he was not particularly impressed by Bacigalupi. As can be seen in the

letter, published here for the first time, Edison brushed Bacigalupi aside. Evidently

Edison considered him so inconsequential that he didn't even bother to sign the letter

himself – he left that for his secretary to do in his name! Unfortunately, no followup

correspondence is known to survive so we have no way to know how Bacigalupi finally

overcame Edison's apparent indifference, but the San Francisco city directory shows

that by 1895 Bacigalupi was operating a store called "Edison's Kinetoscope,

Phonograph and Graphophone Arcade" at 946 Market Street.

Over the next decade Bacigalupi's business grew rapidly. In addition to selling

Edison and Columbia records, Bacigalupi recorded his own. (Reportedly he was the

first to record Billy Murray.) Bacigalupi sold Edison phonographs, Columbia Graphophones,

movie projectors, "drop card" arcade machines, Polyphones, records, films,

horns and other accessories. He also ran a "penny arcade" with Kinetoscopes

and coin-operated phonographs. His name graced phonographs as well as record labels

and even oil bottles. He was definitely a power to be reckoned with.

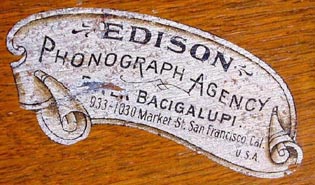

Up to 1898, Bacigalupi used a brass tag to label machines he sold. He soon changed to less expensive decals.

Bacigalupi dealer decals used in 1898 and later. The tag on the left lists "Edison Phonograph & Graphophone Agency." In the late 1890s Bacigalupi stopped carrying Graphophones and changed the decal to remove the term.

Bacigalupi pasted his own labels on top of Edison labels on record boxes. At least 14 different variations are known. The bottle of phonograph oil has Bacigalupi's name and address embossed into the glass.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake was a serious setback, leaving Bacigalupi's

entire business in the rubble. His recollection of the catastrophe, published in

Edison Phonograph Monthly in July 1906, vividly described the experience and did

much to expand his reputation, both at the time and among modern collectors. (The

account can be read HERE).

Although

Bacigalupi rebuilt his business after the earthquake his dominance in the market

declined markedly in subsequent years, in tandem with Edison's. Starting in 1910

the business was renamed Bacigalupi & Sons to reflect the fact that his sons

were now active in the company. As his phonograph sales fell he expanded into musical

instruments. However Bacigalupi's business was never able to regain the importance

it enjoyed prior to the 1906 earthquake, and in 1916 he shut his doors for good.

Bacigalupi's twenty-two years in the business were almost evenly divided between

glory and decline, fading from a phonograph superstar to a historical footnote. He

died in San Francisco on February 22, 1925, at 70 years of age.

Although his

fortunes declined, Bacigalupi's name was ultimately to become legendary among collectors

all over the world. While he may not have impressed Thomas Edison in early 1894 his

legacy has certainly endured in the intervening century.